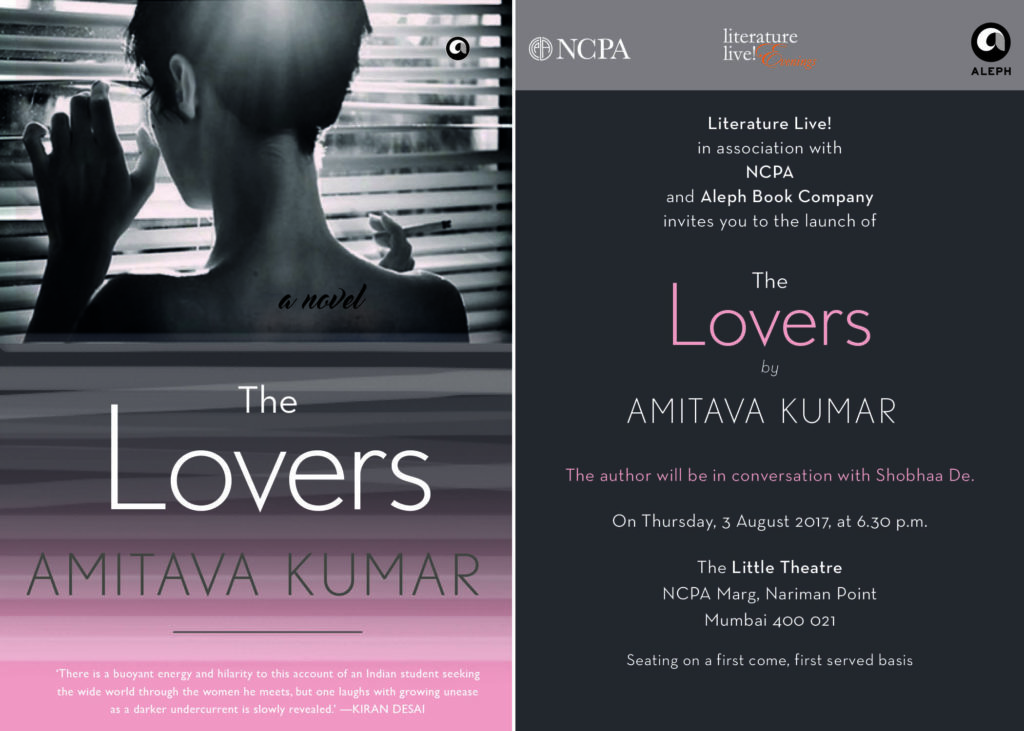

I have returned to my hometown to read from The Lovers as a part of a #BiharKalam event.

I have returned to my hometown to read from The Lovers as a part of a #BiharKalam event.

Here’s what I remember about the love-stories I like–I wrote this in a piece for DailyO:

Let’s talk about favourite lines. That is, let’s talk about what one loves.

Here is a favourite line of mine from a short-story by Junot Diaz: “The half-life of love is forever.”

My brief piece for the Chronicle of Higher Ed’s Lingua Franca on Matthew Desmond’s Evicted. This book won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 2017.

In an author’s note, Desmond has written that often the very people he was studying taught him how to see. Nevertheless, he missed much, at least at first, “not because I was an outsider but also because I was overanalyzing things.” When I read those words, my senses went on alert. I felt that here was a warning for academics. Desmond went on: “A buzzing inner monologue would draw me inward, hindering my ability to remain alert to the heat of life at play right in front of me.” There it was! For me, the definition of the trade book was present in that admission. I’m generalizing wildly, but academic books find safety in explanations that reduce the chaos of social life. To write what is not dead on the page, one has to be open to all kinds of disturbances and challenges and confusion. And skilled writers show us a way (Susan Sontag, Toni Morrison, Denis Johnson, Ralph Ellison, Jesmyn Ward—these are some of Desmond’s models) to draw a more difficult story out of all that pain and frustration.

My review of Arundhati Roy’s novel The Ministry of Utmost Happiness in Bookforum:

On the morning of June 9, 2012, Avtar Singh called 911 in Selma, California, to say that he had killed his family and was about to turn the gun on himself. When the police reached his house, they sent in a robot equipped with a camera. The feed from the robot showed Singh lying dead in the living room. His wife and two sons were also dead; a third son, the eldest, was still breathing, but he died from his wounds five days later. Each person had been shot in the head.

Singh owned a small transport business; he himself drove a truck. But a decade and a half earlier, he had been an officer in the Rashtriya Rifles unit of the Indian army. Major Avtar Singh was in charge of an army camp in war-torn Kashmir, the mountainous region where the Indian army has attempted to quell, often with disturbing brutality, an armed insurrection and calls for democracy. In April 1997, a police investigation had determined that Singh was guilty of abducting and killing a Kashmiri human-rights lawyer, Jalil Andrabi, whose body had been fished out of the Jhelum River. The corpse had torture marks on it—both eyes had been gouged out—and a bullet wound in the head.

Avtar Singh was never arrested for his alleged crimes in Kashmir, and, despite court orders instructing that his passport be impounded, he was able to leave India for Canada and from there reach the United States. In California, during the year prior to the murder-suicide, Singh’s wife called 911 to report her husband’s domestic violence. The incident drew attention to Singh, and journalists in India were soon back on the case. At the time he killed himself, he was facing extradition proceedings.

This is one of several news stories that find elaborate fictional form in Arundhati Roy’s new novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.

My piece for the New Yorker on the attacks on Indians living in America.

On a September evening in 1987, Navroze Mody, a thirty-year-old Indian man living in Jersey City, went for drinks at the Gold Coast Café, in Hoboken. Later that night, after he left the bar, he was accosted on the street by a group of about a dozen youths and severely beaten. Mody died from his injuries four days later. There had been other attacks on Indians in the area at that time, several of them brutal, many of them carried out by a group that called itself the Dotbusters—the name a reference to the bindi worn by Hindu women on their foreheads. Earlier that year, a local newspaper had published a handwritten letter from the Dotbusters: “We will go to any extreme to get Indians to move out of Jersey City. If I’m walking down the street and I see a Hindu and the setting is right, I will hit him or her.”

When I first read about the attack on Mody, I had only recently arrived in the United States.

More.

“Central India’s Ugly Fight for Environmental Justice.” That’s the title of my report from Bastar about a meeting organized by Soni Sori.

If you threw a dart at the heart of India but your aim was off, a little low and to the right, you would hit the village of Matenar, in the administrative division of Bastar, in the state of Chhattisgarh. Though the region’s lush forests once found mention in ancient Sanskrit epics, Bastar now evokes for many Indians the threat or fear of the Naxalites, Maoist guerrilla groups that have waged a fifty-year insurgency against the national government. But Bastar also represents the ugly side of India’s Janus-faced democracy. The place where your errant dart fell is fabled for its mineral wealth, especially iron, coal, tin, and bauxite, and yet its inhabitants, most of whom belong to India’s indigenous population, the adivasis, are among the poorest in the country. Visitors to Chhattisgarh see dense jungle, small huts, and immense mines, but few schools, health centers, or hospitals. New construction seems devoted mostly to four-lane highways—the better to transport government troops into the state and minerals out of it.

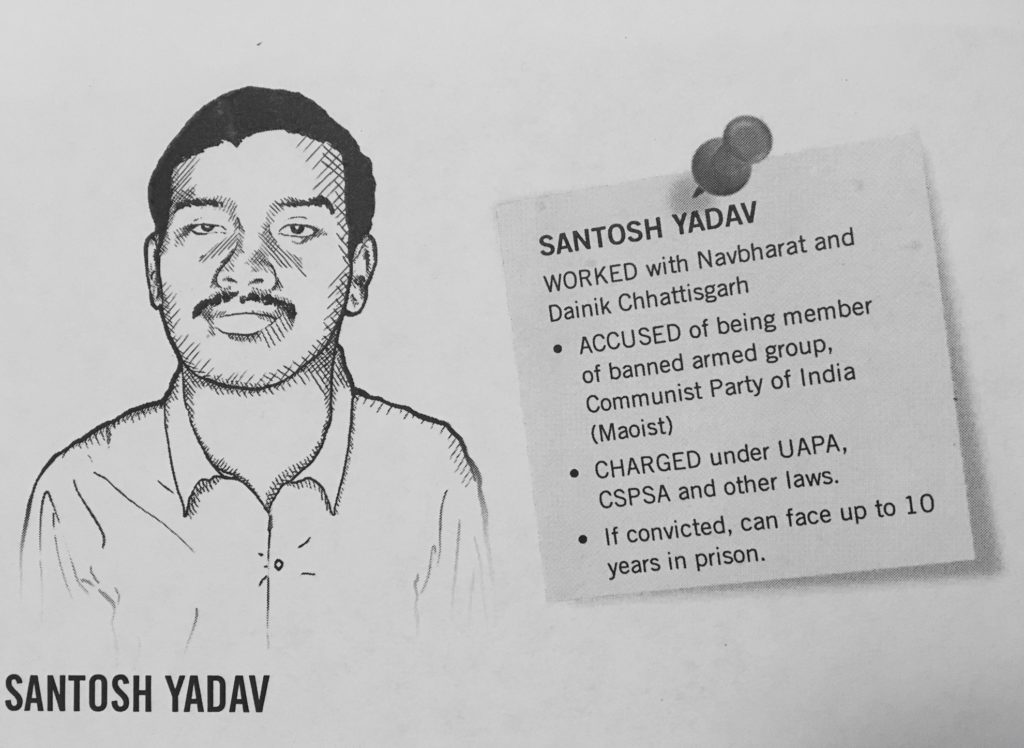

The excellent Indian magazine, Caravan, has published a report I wrote on the repression of journalists in Bastar:

“Yeh raat mein sapna dekh raha tha sarkar ke khilaaf,” Kamal Shukla, a veteran reporter said. I was travelling with him for a few days in Bastar, in December, and Shukla was describing the dire conditions journalists work under in the district. “If the police claimed this about a journalist they had arrested,” he said, “the courts in Chhattisgarh have no right to ask whether the police had proof.”

His younger colleague, who wanted to remain anonymous, added: “If a journalist were to tell even 5 percent of the truth in a newspaper here, black clouds will begin to gather over the individual’s head, prison gates will creak open, and a gift of jan suraksha will be made to him.”

“Jan suraksha,” or, more properly, the Chhattisgarh Vishesh Jan Suraksha Adhiniyam, also known as the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act, refers to a piece of legislation passed by the state assembly in 2005. It allows the police to detain anyone who displays a “tendency to pose an obstacle to the administration of law.” This is the legislation that Shukla was talking about when he said the police has the right to divine one’s dreams and crush dissent. The state of Chhattisgarh has used the legislation to create an atmosphere of fear and repression for journalists, and punish those who dare to stand up to it.

Forthcoming/Monsoon, 2017/Indian subcontinent only/Aleph Book Company. The book will also be published under the title Immigrant, Montana: A Novel by Faber in the UK, Knopf in the US, and in translation by publishers elsewhere.

The review I wrote of Mohsin Hamid’s latest novel, Exit West, appears in the new Bookforum (Feb/Mar, 2017). My thanks to the model in the top picture–he was home the day the magazine arrived because school had been cancelled due to snow.