In my latest blog for The Chronicle’s Lingua Franca, I write about the widespread suspicion of self-help books and also why it might makes sense for serious writers to write in that genre:

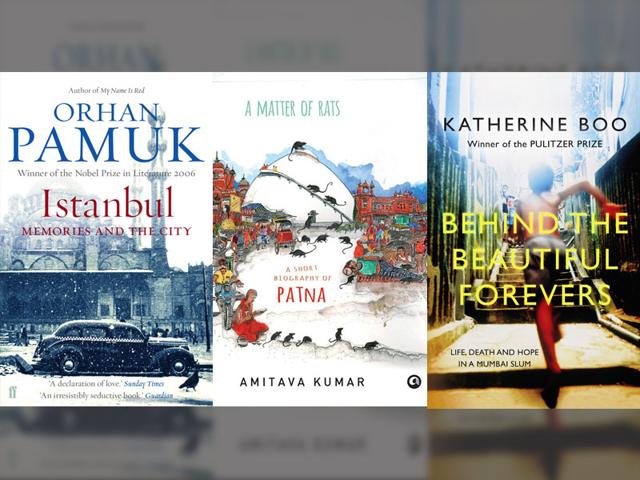

In 1997, Alain de Botton published his book How Proust Can Change Your Life. I was charmed by it. I remember using it in a course on cultural criticism for a graduate class that had a mix of theorists and creative writers. I thought of de Botton’s book as a model we could adopt. Here was an original work of criticism that taught me something about Proust while it playfully adopted a popular or low-brow form of writing — that is, the self-help book.

Like every other self-respecting academic, I’m distrustful of self-help books. In my hometown in India, at the bookstore where I once bought a Saul Bellow novel as a teen, mostly textbooks are sold now. And self-help books, immediately recognizable because of their lurid covers, promising a bright future. Learning is replaced by the reading of instruction manuals; change narrowed to individual striving; all of human emancipation instrumentalized, reduced to the acquisition of a better attitude or a few simple skills.