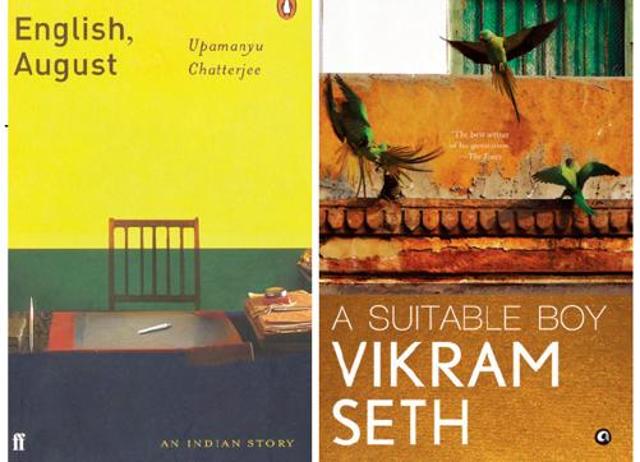

In my latest The Bookist column for HT Brunch, I have reviewed the literature that is critical of the nation-state and its violence.

If the police were to burst into your room while you were sleeping and, putting a gun to your head, ask you to name a literary work that was critical of the idea of the nation, which title would you reveal?

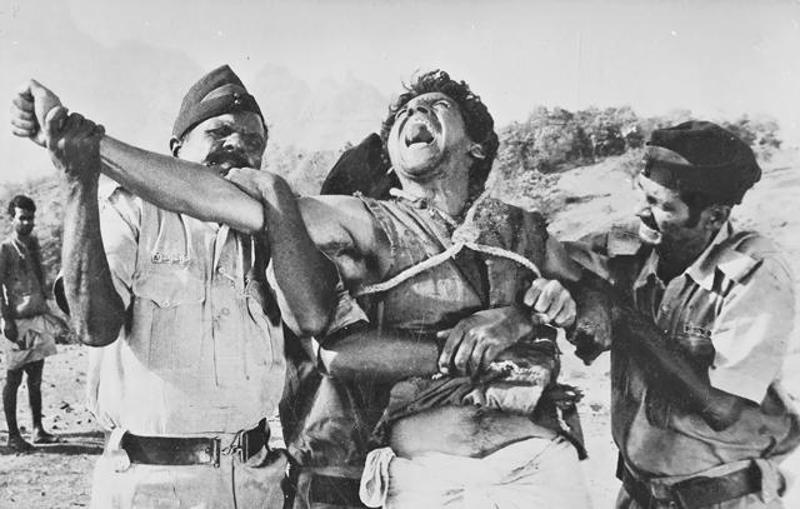

Those who read Saadat Hasan Manto in school will go back to that early memory. We all remember Toba Tek Singh: the occupants of the lunatic asylum not being able to comprehend the Partition, and the old Sikh Bishan Singh dying in no man’s land between the borders of the two countries, unable to decide where he belonged.

But the memory of this story is for me mixed with the white of my school uniform, the safety of home, and the taste of cornflakes in the morning. Which means the call of the nation begins to seem merely like nostalgia for lost childhood. Nationalism in this scenario becomes only an appeal to sentiment.

Let us go further afield, then, to a far country, to look for the literature of sedition.