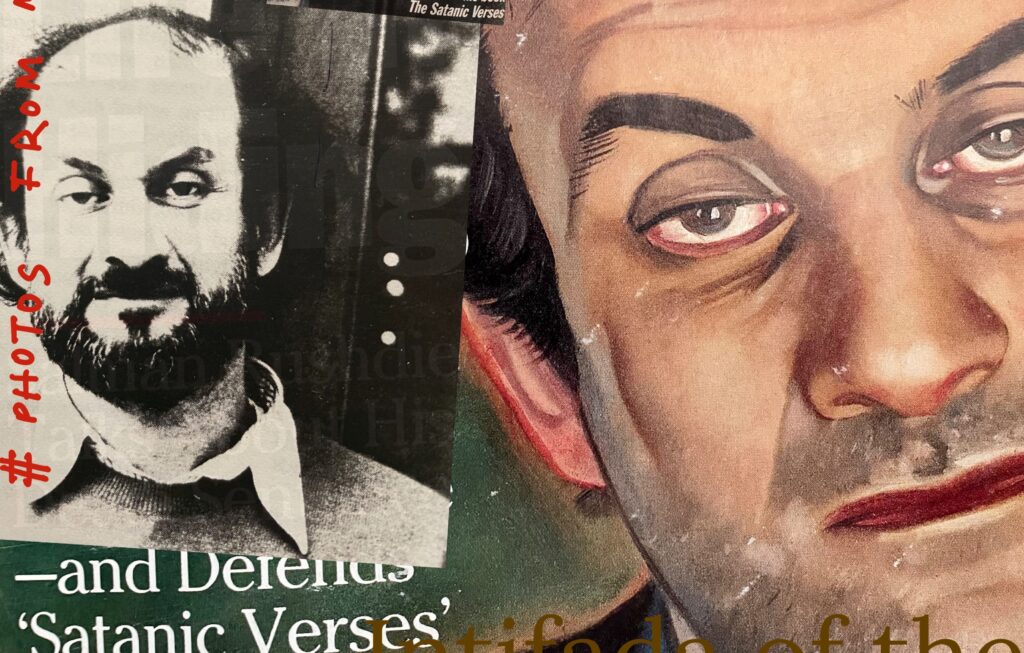

My open letter to Salman Rushdie’s would-be assassin in The Indian Express. Link here.

An Open Letter to Hadi Matar

Sub-heading: On Friday, a 24-year-old from New Jersey named Hadi Matar attacked the writer Salman Rushdie with a knife. Another writer wants the would-be assassin to know more about the man he tried to kill.

Listen, you are young and I understand you will only be sitting in a room doing nothing for many, many years. I hope you will find time to read this letter.

The world learned yesterday that you are twenty-four. The man you tried to kill is seventy-five. I don’t know about you but when I was twenty-four I was reading that’s man’s writings with great devotion. You might even say I was a bit fanatical in my habit.

The following year, when I was twenty-five, there was a fatwa issued by Ayatollah Khomeini, calling for this man’s death for his novel The Satanic Verses—and that murderous edict resulted, after three decades, in the terrible act you perpetrated with such savagery. The man you tried to kill survived your attack; I’m guessing that now there will be no bounty for you. Only an eternity in prison.

I’m just pointing out the basic facts here. As the man you tried to kill might put it, in his own light-hearted way, it didn’t turn out to be such a profitable investment for you.

I apologize. I sound petty. When I sat down to write this letter, I hadn’t intended to be bitter. In fact, I wanted to meet you with my own twenty-four-year-old self. That particular version of myself would want you to read books. Instead of listening to old men railing from the pulpit, men who believe they carry the word of God, and who decide who can live or die—instead of listening to them, will you not heed more human voices?

Let me begin with the voice of the man you tried to kill.

After that appalling fatwa, issued on Valentine’s Day, the writer went into hiding. He lived in safehouses under police protection. On the first anniversary of the fatwa, in a short poem that he published in Granta magazine, he wrote that he wanted to “sing on, in spite of attacks, / to sing (while my dreams are being murdered by facts) / praises of butterflies broken on racks.”

You will perhaps grasp the brutality, but do you also see the beauty? That image of butterflies broken on instruments of torture is so striking and so powerful that I see at once why the great literary critic Edward Said once commented that the man you tried to kill represented “the intifada of the imagination.”

Ten years after the fatwa, in a piece in The New Yorker entitled “My Unfunny Valentine,” the writer who you tried to kill stated that he was now going to write only of love. “Love feels more and more like the only subject. At the center of my life, of my new work, of my future plans, I now find nothing else.”

Can you imagine what it meant for a young man, a little older than you, to be given the gift of such words to shape his own identity as a writer?

Do you read? I ask not to diminish you or humiliate you, but to offer an invitation. It hurt me terribly some years ago to learn that the killer of a writer in India had never read the woman he had shot to death. The dead writer was a journalist of enormous courage. Her killer was paid ten thousand rupees by people who told him nothing more than that this woman was hurting their religion. This writer’s name was Gauri Lankesh. The man who killed her, Parshuram Waghmare, was only two years older than you are now when he committed the murder. He is in prison. Forces of fundamentalist belief, who use religion as an excuse for destroying lives, have been unleashed in different parts of the world. It is a threatening feature of the apocalyptical landscape of modern geopolitics.

Like the man you tried to kill, I too am a writer. As my life has been given over to reading and writing books, I hold on to the belief that if we read widely and deeply, we will encounter people and places unlike ourselves. This sense of difference, its pleasures and challenges, will perhaps steer us away from intolerance. Many people in this country, including Malcolm X, discovered reading in prison—and were transformed. I hope that you too will find a similar liberation in learning.

We have seen the universal outpouring of grief and concern for the man you tried to kill—but there’s a further point I’m trying to make. People have been posting his lines on social media, they are discussing the influence of his work. Over the past thirty or forty hours, I have read nothing but his words in essays, novels, and interviews. (My son, only twelve, has declared his interest in reading The Satanic Verses. I think he should wait.) Do you see what I’m getting at? You have failed—as any act of violence, and in such circumstances, inevitably would—because you have succeeded only in returning us to his words.